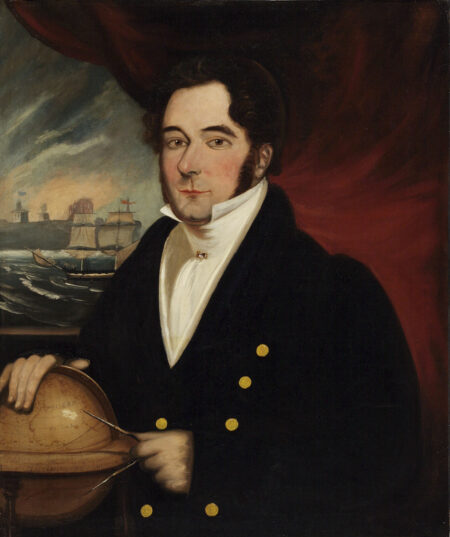

John Franklin

Explorer

Modern

Quick Facts:

He is known for mysteriously disappearing while leading an expedition in search of the Northwest Passage, a waterway that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in northern Canada

Introduction

In the late 19th century, there were several British expeditions launched to search for the Northwest Passage, a waterway through Canada believed to have connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. One of the most well known of those expeditions was in 1845, led by Sir John Franklin. Although Franklin did not discover the Northwest Passage before his disappearance, he was one of the first to map the northern coastlines of Canada in the Arctic.

Biography

Early Life

John Franklin (later known as Sir John Franklin) was born on April 16, 1786, in Spilsby, England. He grew up in a large family, and was the ninth child of 12 born to Willingham Franklin and his wife Hannah. Franklin began his education at a young age. He first attended a preparatory school at St. Ives in Huntingdonshire. Then, at the age of 12, he attended Louth Grammar School. As a young man, Franklin had a great interest in sea travel and exploration, although his father did not approve of that lifestyle. Yet, Franklin was allowed to accompany a merchant ship traveling from Kingston to Lisbon. After the journey was complete, Franklin was appointed to the British Royal Navy at age fourteen. In 1800, he joined the crew of HMS Polyphemus as a first class volunteer.1

Soon after joining Polyphemus, Franklin was re-appointed as a midshipman on Investigator on April 27, 1801. The Investigator set out to explore the previously uncharted coasts of Australia for two years. The journey ended abruptly when the vessel became unseaworthy and was abandoned. Franklin returned home on a different ship in 1804. In 1805 Franklin was appointed to Bellerophon which participated in the blockade of Brest and the Battle of Trafalgar during the Napoleonic Wars. Then, in 1807, Franklin joined the ship Bedford which took part in the Battle of New Orleans. Franklin remained on Bedford until it returned home at the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

Voyages

Principal Voyage

After the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, the British Royal Navy sought to explore parts of the Arctic again. In 1818 Franklin served under David Buchan on a new expedition north. Buchan commanded the HMS Dorothea, while Franklin was given charge of HMS Trent. The goal was to discover a passage north between Greenland and Norway, around the north pole, to the Bering Strait on the other side.2 Buchan’s ships sailed from England on 25 April 1818. The expedition was unsuccessful, and called off in six months. They had spent weeks trying to break through the ice northwest of Spitsbergen in northern Norway. Though they were equipped for winter in the Arctic, the ice had proved to be heavy, and Buchan’s ship Trent had sustained heavy damage.3 They returned to England in October.

After the unsuccessful voyage to seek a passage in the Arctic Sea, another expedition to find the Northwest Passage along the northern coast of North America set out in 1819. Franklin’s party was tasked with mapping the northern coastline and sailing into the Coppermine River to see if that area was possibly the Northwest Passage. Throughout the voyage, Franklin experienced shortages of supplies and crew, forcing the journey to end in 1822, much earlier than planned. Although this voyage was also unsuccessful, Franklin did not give up trying to find the Northwest Passage. His efforts did not go unnoticed. His family status plus his service to the Royal Navy earned his knighthood. He was knighted in 1839, and became known officially as “Sir” John Franklin.

Subsequent Voyages

Sir John Franklin’s most famous expedition took place in 1845. Franklin was determined to discover the Northwest Passage on this journey. The expedition party included two ships, HMS Erebus – commanded by Franklin himself – and HMS Terror, carrying a total of 134 men. The party departed from the River Thames in London on May 19, 1845. This time around, Franklin did what he could to ensure the party was well supplied and prepared for the long journey ahead. Their objective was to discover the Northwest Passage within a year, and had enough provisions for at least three years.4 They stopped along the coast of Greenland, where Franklin wrote several letters stating they were hopeful of their journey. These would be the last recorded correspondences from Franklin and his crew. Franklin commanded the party to sail towards the Wellington Channel and the Barrow Strait in Northern Canada. Records show that Franklin and his expedition were last seen on July 26, when they sailed into Baffin Bay. There, they mysteriously disappeared.

Later Years and Death

It is believed that both Erebus and Terror became trapped in ice for almost two years. Early accounts assumed the ships eventually sank, killing Franklin and all crew-members. Recovered journals from crew members were later found. In them, they claim that Franklin died of unknown causes aboard Erebus on June 11, 1847.5 The men abandoned the ships, and went on foot into the harsh Arctic terrain in search of rescue.There are no known survivors from the remaining members of the expedition. After the disappearance of Franklin and his party, there were around 30 other expeditions sent out to search for the missing men.

Legacy

Sir John Franklin never discovered the Northwest Passage himself. Yet, the numerous expeditions sent looking for him and his missing party uncovered more and more unexplored islands and passages above North America. Franklin was an intrepid explorer who was one of the first to venture into the Arctic, one of the most unknown and, therefore, dangerous places. In September 2014, a Canadian expedition team found the wreck of Erebus southwest of King William Island; two years later, Terror was found, nearly 60 miles away in Terror Bay.6

Images

- Print of “The Arctic Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin” (Credit The Mariners’ Museum Collection – catalog# 1936.0716.000001

- North-West Searching Expedition for Sir John Franklin, Sir John Ross’ Yacht “Felix” At Anchor in Loch Ryan (Credit: The Mariners’ Museum – Catalog# 2017.0009.000001)

- Print of the vessel “Advance” frozen in the ice while searching for the Franklin expedition party. The ship was abandoned by Elisha Kent Kane in 1855 and was presumably crushed by the ice pack. (Credit: The Mariners’ Museum – catalog# 1933.0952.000001)

Endnotes

- Albert Hastings Markham, Life of Sir John Franklin and the North-west Passage. (London: G. Philip & Sons, 1891), 10.

- Janice Cavell, “Franklin, Sir John,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, accessed April 15, 2020, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/franklin_john_7E.html.

- Ibid.

- Henry Duff Traill, The Life of Sir John Franklin, R.N. (London: J. Murray, 1896), 336.

- Ibid., 367.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sir John Franklin,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed April 12, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Franklin.