Backstaff

Tool

Age of Discovery

Quick Facts:

Similar to a cross-staff, the backstaff uses the shadow of the sun instead of the direct view of the sun to obtain the altitude.

Introduction

Backstaff is the name given to any instrument that measures the altitude of the sun by the projection of a shadow. Invented by John Davis in the 16th century, it became a useful tool for navigators at sea. Tools before the backstaff often forced navigators to stare into the sun, which lead to bad eye-sight, or even blindness. The benefit of the backstaff is that the user relied on the sun’s shadow, rather than having to look directly at it, to find your measurement.

History

The backstaff was a navigational tool that measured altitude using the sun. Most tools of this time required a navigator to stare into the sun to find measurements, often causing them to eventually lose their sight. Back-sight tools like the backstaff made taking measurements possible without having to look directly at the sun. Navigators began using tools, like the cross-staff, backwards. The user would turn his back to the sun, and adjust so that the shadow fell on the horizon vane.1 The navigator could sight the horizon and measure the height of the sun at the same time. It was this new method that led to the development of the back-staff. There are many versions of the backstaff. But the invention of the best version is credited to English sea captain John Davis around 1594.2 Davis was exploring North American waterways searching for a Northwest Passage through the Arctic to the Pacific Ocean. On his journey, he invented the backstaff as a way to improve on other instruments such as the quadrant and the cross-staff. Because of this, the back-staff is also known as the “the Davis quadrant.”3

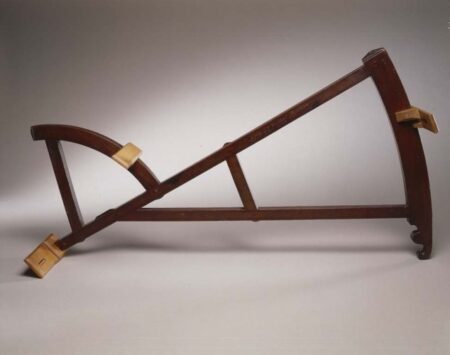

Backstaffs were typically made with a dark wood such as ebony or rosewood.4 It was generally a triangle shape with adjustable vanes – used for sighting; and two arcs – used for taking angle measurements. One arc was 30 degrees, the other was 60 degrees.5 This instrument became very popular. They were manufactured in several places including Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, and North America.6 One main problem with using the backstaff is that it can really only take measurements using the sun. With no strong shadow to rely on, it is not as useful at night using stars. The backstaff continued to be used by mariners for over 150 years. By the mid eighteenth century, however, it became replaced by more reliable instruments such as the octant and sextant.

How It Works

Backstaffs find altitude by measuring the angle between the horizon and the sun. Unlike previous instruments, however, navigators relied on the sun’s shadow rather than looking directly at it. Navigators could do this using the key parts of the instrument. The shadow vane on the small arc used to cast a shadow; the horizon vane on the larger arc was where you view the horizon; and the sighting vane was the slit the observer would look through. So how does it work?

To use the backstaff, the navigator with his back to the sun, holds the instrument in front of his and places it on his shoulder. To find the altitude, the navigator would move the vanes along the arcs, and view the horizon through a small slit. They would move the shadow vane on the smaller arc until the edge of the vane casts a shadow on the slit of the horizon vane. While doing this, the navigator would also look through a peephole in the vane on the larger arc and through a slit in the horizon vane to view the horizon. This allows the navigator to find the altitude of the sun by viewing the horizon and the sun’s shadow at the same time through the horizon vane.7

Endnotes

- Peter Ifland, Taking the Stars: Celestial Navigation from Argonauts to Astronauts (Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company, 1998), 9.

- Gerard L’Estrange Turner, Scientific Instruments, 1500-1900: An Introduction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 31.

- Jack Lagan, A B Sea: A Loose-Footed Lexicon (New York: Sheridan House Inc., 2003), 28-29.

- John Robinson and George Francis Dow, The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607-1907 (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2007), 47.

- Turner, Scientific Instruments, 31.

- W. F. J. Mörzer Bruyns and Richard Dunn, “The Backstaff, or Davis Quadrant,” Sextants at Greenwich: A Catalogue of the Mariner’s Quadrants, Mariner’s Astrolabes Cross-staffs, Backstaffs, Octants, Sextants, Quintants, Reflecting Circles and Artificial Horizons in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (London: Oxford University Press, 2009), par. 6.

- Jeanne Willoz-Egnor, “Back-staff,” The Institute of Navigation, Accessed August 08, 2018, https://www.ion.org/museum/item_view.cfm?cid=6&scid=13&iid=31.

Bibliography

Bruyns, W. F. J. Mörzer, and Richard Dunn. “The Backstaff, or Davis Quadrant,” Sextants at Greenwich: A Catalogue of the Mariner’s Quadrants, Mariner’s Astrolabes Cross-staffs, Backstaffs, Octants, Sextants, Quintants, Reflecting Circles and Artificial Horizons in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. London: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Ifland, Peter. Taking the Stars: Celestial Navigation from Argonauts to Astronauts. Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company, 1998.

Lagan, Jack. A B Sea: A Loose-Footed Lexicon. New York: Sheridan House Inc., 2003.

Robinson, John, and George Francis Dow. The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607-1907. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2007.

Turner, Gerard L’Estrange. Scientific Instruments, 1500-1900: An Introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Willoz-Egnor, Jeanne. “Back-staff.” The Institute of Navigation. Accessed August 08, 2018. https://www.ion.org/museum/item_view.cfm?cid=6&scid=13&iid=31.