Francisco Pizarro

Explorer

Age of Discovery

Quick Facts:

Francisco Pizarro contributed to the Spanish empire gaining control over South America by conquering the great Inca Empire in Peru

Introduction

The promise of wealth and adventure in the New World led to Francisco Pizarro to becoming one of Spain’s most victorious conquistadors (Spanish for “conqueror”). Pizarro took several expeditions throughout South America, gaining land and wealth for Spain. His journeys took him across the Atlantic Ocean, through tropical jungles, over mountains, and across the coastal deserts of South America.1 He is best known for his killing of the Inca king, Atahualpa, and conquering the Inca Empire. But what he really did was establish Spanish roots for the conquest and colonization of Peru.

Biography

Early Life

Francisco Pizarro was born around 1475 in Trujillo, Spain. The town of Trujillo was in the Extremadura region of Spain, the same place where famed explorer Hernando de Soto was from. Pizarro came from a poor family. He was the son of Gonzalo Pizarro Rodríguez de Aguilar, an army officer, and Francisca González Mateos, a servant. Because his parents never married, he was an illegitimate son. Pizarro’s father would go on to have two other illegitimate sons, and Pizarro’s brothers would later play in role in the conquest of Peru. Sadly, neither of his parents gave Pizarro much attention. Young Pizarro did not receive a good education, and he never learned to read or write.2 Instead, he began working at a young age as a swineherd – someone who raised and took care of pigs. This a common job in his region that was very dirty work, but provided some money for food and clothing. Pizarro, however, had bigger dreams of adventure, excitement, and most importantly, wealth. So as a teenager, Pizarro joined the Spanish army. The skills he would learn in the army would help him in his fighting and conquests in South America.

Pizarro spent much of his time as a soldier in Italy where it is said he gained a reputation for being courageous.3 Pizarro was in his late teens when famed explorer Christopher Columbus landed in the New World in 1492. Like several other European countries during this time, Spain quickly expanded their empire to new colonies in the Caribbean and South America. The voyages of Columbus and the promise of riches excited many, including young Pizarro. Around 1502, ten years after Columbus sailed, Pizarro left Spain and sailed to Hispaniola. Hispaniola today is composed of the two nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The island of Hispaniola was a Spanish outpost where Pizarro served in the military troops for a few years. However, he still dreamed of exploring the New World. Pizarro would soon get the opportunity for adventure that he longed for.

Voyages

Principal Voyage

In 1510, Pizarro joined Alonso de Ojeda and 300 other settlers on an expedition to start a colony on the coast of South America.4 They colony they established was named San Sebastian (in present day Colombia). After the colony was settled, Ojeda returned to Santo Domingo in Hispaniola for additional supplies. Francisco Pizarro was left in charge during Ojeda’s absence. Many of the settlers became sick and died from tropical diseases they caught in the jungles. Of the 300 settlers who originally joined the expedition, 200 died from illness, starvation, and native attacks.5 Pizarro and the other San Sebastian survivors abandoned the settlement and set up a new colony at Darien, in what is now Panama. He became friends with the colony’s new leader – and soon to be famous explorer – Vasco de Nuñez de Balboa. In 1513, Pizarro was Balboa’s second in command during their trek westward across Panama to discover the South Sea. Balboa, Pizarro, and their men were the first Europeans to see the South Sea, today called the Pacific Ocean.

The following year Pizarro began to serve the new governor of Panama, Pedrarias Dávila. In 1519, Pizarro was ordered to arrest Balboa, Dávila’s rival. Balboa was arrested and later executed. Pizarro was rewarded and eventually gained a fair amount of wealth and land, thus giving him status in the New World. He held the position of mayor of Panama City for several years afterwards. Pizarro still desired more power and wealth. Pizarro developed a friendship and partnership with fellow soldier Diego de Almagro. They prepared an expedition for discovery and conquest down the west coast of South America. Together, they set out in search of riches in South America. Pizarro sailed from the Bay of Panama in November 1524,6 into the Biru river, which he followed for several days. Running low on supplies, they stopped at the Isle of Pearls just south of Panama for provisions. They encountered friendly natives who gave the Europeans food, but the Europeans also stole much of their gold. They continued sailing southward, encountering bad weather along the way. Their vessel needed repair, so they returned to the Bay of Panama with the gold they had gained. Before returning, they named the land Peru, most likely after the name of the Biru River.7

Subsequent Voyages

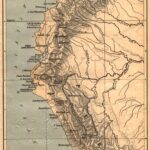

Pedrarias did not allow Pizarro to continue his explorations. So Pizarro left South America in spring of 1528 to return to Spain. Here, he petitioned Emperor Carlos V to allow his plans for further exploration and conquest of Peru. The emperor not only gave Pizarro permission to continue his conquests, but gave him a coat of arms and other honors as well. In July 1529, Pizarro was made governor and captain general of the New Castile province, an area south of Panama along the newly discovered coast.8 He returned to Panama in 1530, and set sail for Peru in January 1531. He had one ship, although two more would join him later, 180 men – including four of his brothers, and 37 horses.9 They arrived in Peru and set up camp which they named San Miguel.

Fellow explorer Hernando de Soto had joined Pizarro’s expedition. De Soto scouted ahead and reported that the were in the middle of a civil war. Pizarro requested a meeting with the Inca ruler Atahualpa. Atahualpa finally agreed to a meeting in the city of Cajamarca, and Pizarro arrived there in November 1531. The Spanish tried to convert Atahualpa to Christianity. He refused, and soon war broke out between the Inca and the Spaniards for several years. The Spaniards Pizarro and his men defeated the Inca army, Pizarro himself capturing the Inca ruler. Pizarro demanded they be given all of their gold and treasure for Atahualpa’s freedom. Despite the Inca giving them the riches, Pizarro still had Atahualpa killed in 1533.10 The Inca armies retreated, and the Spanish army continued onward to the Inca capital of Cuzco. Pizarro and his army entered the city, and soon conquered the rest of the Inca army and took over the capital. He sacked the city and robbed its weather. The remaining Inca natives were either killed or enslaved. The great Inca empire had come to an end.

Later Years and Death

Francisco Pizarro spent the next several years maintaining the Spanish control of Peru. Pizarro and his partner, Almagro, experienced years of tension and rivalry. Almagro felt he should have some power in Cuzco. The two constantly fought for control of the city, and Pizarro eventually had Almagro imprisoned and executed in 1538. Pizarro continued his explorations, and even founded the city Lima, Peru. Still upset at Pizarro’s decision to have Almagro killed, several of Almagro’s followers avenged his death a few years later. They attacked his palace, and killed Francisco Pizarro in Lima on June 26, 1541.11

Legacy

Francisco Pizarro increased Spain’s hold in South America. His desire for wealth and power drove him to become one of the greatest conquistadors of the New World. His capture and execution of the Inca ruler lead to the end of the Inca empire. While this was a proud achievement to him, today we understand that this was an unfortunate event that wiped out an entire culture. The enslavements and death from Spanish diseases caused the native population to decline by millions over the course of a few decades. Nonetheless, Pizarro helped explore and colonize several parts of South America. His achievements are still seen today. The city Lima which Pizarro named and established is the capital of Peru today.

Endnotes

- John Paul Zronik, Francisco Pizarro: Journeys Through Peru and South America (New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2005), 4.

- Barbara A. Somervill, Francisco Pizarro: Conqueror of the Incas (Mankato: Capstone Press, 2008), 17.

- George Cubitt, Pizarro: or, The Discovery And Conquest of Peru (London: John Mason, 1849), 35.

- Lynn Hoogenboom, Francisco Pizarro: A Primary Source Biography (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2006), 4.

- John Paul Zronik, Francisco Pizarro, 8.

- Manuel José Quintana, Lives of Vasco Nunez de Balboa, and Francisco Pizarro (London: William Blackwood, 1832), 93.

- Cubitt, Pizarro, 45

- Kenneth Pletcher, ed., The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009), 94.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide, 94.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 65.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide, 96.

Bibliography

Cubitt, George. Pizarro: or, The Discovery And Conquest of Peru. London: John Mason, 1849.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Hoogenboom, Lynn. Francisco Pizarro: A Primary Source Biography. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2006.

Somervill, Barbara A. Francisco Pizarro: Conqueror of the Incas. Mankato: Capstone Press, 2008.

Pletcher, Kenneth ed. The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009.

Quintana, Manuel José. Lives of Vasco Nunez de Balboa, and Francisco Pizarro. London: William Blackwood, 1832.

Zronik, John Paul. Francisco Pizarro: Journeys Through Peru and South America. New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2005.

Gallery

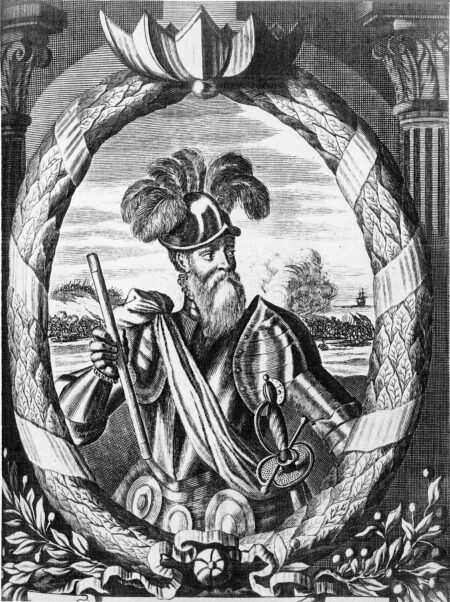

- Pizarro preparing to leave on his third expedition in 1530. The Mariners’ Museum E141 .B91

- Map showing Pizarro’s January 1531 – November 1533 route from Panama to Cuzco. William Robert Shepherd, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons