Jacques Cartier

Explorer

Age of Discovery

Quick Facts:

French navigator and explorer credited with naming Canada, exploring the St. Lawrence River, and Canadian areas that would become French territory

Introduction

Jacques Cartier is best remembered for his exploration of parts of Canada. We even credit him with giving the country its name. Although Cartier named the land he traveled to “Canada,” the word actually comes from the Iroquois-Huron language. These natives referred to their village of Stacona as a kanata – which simply means “village” or “settlement”.1 Cartier used this word to refer to all of the areas he explored, and soon would be used globally as more of the French came to explore the land.

Biography

Early Life

Jacques Cartier was born on December 31, 1491 in Saint-Malo, a port town of Brittany, France. His father was Jamet Cartier, and his mother was Geseline Jansart.2 Almost nothing is known of his early life before his famous explorations. Saint-Malo was a fishing town in northern France.3 So young Jacques probably learned navigational skills and seafaring early in life. Many scholars believe that Cartier took several trips across the Atlantic Ocean in his early years. Many agree that Cartier sailed on a voyage to Brazil as a young man.4 However, there is no specific evidence to support this. In May 1519, Cartier married Catherine des Granches. Catherine came from a higher class than Cartier.5 So when they married, Cartier’s social standing and position in society increased.

Cartier quickly became an experienced navigator and sailor. Many historians believe that Cartier joined Giovanni da Verrazzano on his voyages to the New World in 1524 and 1528. At this time, the Spanish and Portuguese were finding land, resources, and wealth in the New World. Other countries, like England and France, wanted to find new discoveries and wealth in the New World as well. So they sent out explorers to claim land for them. King Francis I of France wanted an expedition to go explore the New World for land and riches. He also wanted to find a Northwest Passage to Asia. Jacques Cartier was chosen to lead this venture.

Voyages

Principal Voyage

The voyage began on April 20, 1534 when Cartier departed from Saint-Malo with 2 ships and 61 men. After just 20 days of sailing, the expedition reached the area that is now modern day Newfoundland by early May. The fleet sailed north along the coastline for a short while, before turning around and heading south. Cartier continued to explore the western coastline of Newfoundland. After passing through the Strait of Belle Isle. Cartier and his fleet explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In June of 1534 he made his first major discovery when he came upon an area we know today as Prince Edward Island.6 This is a large island that is still part of modern day Canada. After landing on Prince Edward Island, Cartier’s expedition explored the gulf and various inlets nearby in search of a passage to Asia. Failing to find the passage, they sailed onward. They explored Chaleur Bay, then headed northward. The final spot Cartier landed before returning to France was on the modern day Gaspé Peninsula. Here, they met the friendly Mimac (also spelled Mi’kmaq) natives who lived in the area, and traded furs and other items.7 The expedition sailed around Anticosti Island before continuing out of the St. Lawrence Gulf. This made Jacques Cartier the first person to sail completely around the gulf.8 They set sail to return home, and reached Saint-Malo, France on September 5, 1534.

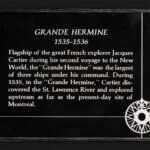

After Cartier returned to France and met with King Francis, a second voyage to North America was funded. Both Cartier and the king were excited by Cartier’s findings during his first voyage and felt that his discoveries were promising. The king gave Cartier more ships and men for the voyage. They were tasked with exploring more of the mainland of the newly discovered places. Cartier and his men left France on May 19, 1535. Cartier had three ships – La Grande Hermine, La Petite Hermine, and L’Emerillon.9 The expedition eventually reached Funk Island off of Newfoundland’s coast. On September 7, 1535, Cartier and his men reached the site of the present day city of Quebec. They stopped at a village called Stadacona, where they were greeted by the Donnaconna, chief of the Huron natives.10 Several Huron natives went with Cartier as guides. They sailed up the St. Lawrence River, and on October 2, 1535, reached Hochelaga (now Montréal). The natives told Cartier of a place with riches called Saguenay, but it could not be reached by Cartier’s large ships. So he and his men returned to the mouth of the St. Charles River, to a fort they had previously built named Saint Croix. By November, the waterways were frozen. So Cartier and his men spent this winter here until April 1536. During winter, many of the men got sick with scurvy and died. Before returning to France, Cartier kidnapped Donnaconna and his two sons so he could tell King Francis I of the riches of Saguenay in person. May 6, 1536 Cartier set sail for France.

Subsequent Voyages

Cartier was given permission to take a third voyage to find the land of Saguenay. But it would be five years before the expedition left. This time, a man named Rocque de Roberval would be in charge. Roberval’s team was to meet Cartier’s expedition in North America the following year after a settlement was begun. May 23, 1541, Cartier, with his men and five ships, left Saint Malo, France. The goal of the expedition was to establish a settlement in North America. They arrived in Stadacona on August 23, 1541, and established a settlement named “Charlesbourg-Royal” (near modern day Quebec City). They began exploring the area. Soon, Cartier and his men believed found stones that looked like diamonds and gold. However, it turned out that the diamonds were actually pieces of quartz, and the gold was iron pyrite – better known as “fool’s gold.”11 Cartier and some of his men went back to Hochelaga. Some Huron natives then went with Cartier’s team to find Saguenay. But they never found it, so Cartier and his men returned to Charlesbourg-Royal where they spent winter. By spring, the native’s and the French relations turned hostile. The French abandoned the settlement, and left in June 1542.

Later Years and Death

After leaving Charlesbourg-Royal, Cartier’s fleet met Roberval in St. John’s harbour in Newfoundland. He had with him barrels of the “diamonds” and “gold” which he would later find to be worthless. Roberval ordered Cartier and the settlers to turn around and go back to the settlement. But they refused. Cartier and the colonists slipped away one night, and headed back to Saint Malo. They reached home in October 1542. Cartier’s exploration career came to an end after his third voyage to North America. He remained in France during the last years of his life managing his estate. He died September 1, 1557 at the age of 66.

Legacy

Jacques Cartier is credited with discovering and claiming the land now known as Canada for France. However, his treatment of the natives of the area was not always great. Throughout his three voyages, Cartier became the first European to explore the St. Lawrence Gulf and St. Lawrence River. Although his attempt to establish a French colony near modern day Quebec City was a failure, his discoveries led to further European exploration through the 16th and 17th centuries. The French would go on to colonize the area, and establish a rich fur trade. Several places in Canada honor him, including the Jacques Cartier Bridge that crosses the St. Lawrence River from Montreal to Longueuil, Quebec. And a statue of the explorer stands at the explorer’s birthplace of Saint Malo, France.12

Images

- “Jacques Cartier,” The Mariners’ Museum E133.C3.S8.

- Reverse of silver ingot showing description La Grande Hermine,” flagship of Cartier’s North American journeys. The Mariners Museum 1974.0001.000014.

- Front of silver ingot showing “La Grande Hermine,” flagship of Cartier’s North American journeys. The Mariners Museum 1974.0001.000014.

- A painting representing a side picture of explorer Jacques Cartier. No known paintings of Cartier were created during his lifetime. Théophile Hamel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Endnotes

- Meg Greene, Jacques Cartier: Navigating the St. Lawrence River (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2004), 54.

- James Phinney Baxter, Jean François de La Roque Roberval, and Jean Alfonce, A Memoir of Jacques Cartier, Sieur de Limoilou: His Voyages to the St. Lawrence, a Bibliography and a Facsimile of the Manuscript of 1534 with Annotations, Etc. (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1906), 11.

- Jeff Donaldson-Forbes, Jacques Cartier (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2006), 5.

- Donaldson-Forbes, Jacques Cartier, 6.

- Baxter, et. al, A Memoir of Jacques Cartier, 12-13.

- James Stuart Olson, Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), 118.

- Kristin Petrie, Jacques Cartier (Edina: ABDO Publishing Company, 2004), 9.

- Alan Day, Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Passage (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2006), 46.

- Day, Historical Dictionary, 46.

- Richard E. Bohlander, ed., World Explorers and Discoverers (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992), 101.

- Bohlander, World Explorers and Discoverers, 103.

- Jennifer Lackey, Jacques Cartier: Exploring the St. Lawrence River (New York: Crabtree Publishing Company, 2006), 30.