Walter Raleigh

Explorer

Age of Discovery

Quick Facts:

British explorer who sponsored the first attempt to found a permanent English settlement at Roanoke Island, and later sought to find the legendary city of El Dorado.

Introduction

Sir Walter Raleigh (also spelled Ralegh, Rawleigh) was an English explorer, soldier, poet, and writer. He funded three voyages to Roanoke Island, North Carolina (off the present-day Outer Banks). Although the colony was not a success, it did pave the way for further English colonization in the New World. He later led two unsuccessful expeditions to South America in search of the fabled city of gold – El Dorado.

Biography

Early Life

Walter Raleigh (later earning the title Sir Walter Raleigh) was born around 1554, although there is no exact recorded date of his birth. He was born at the house of Hayes Barton, Devon, England. His parents were Walter Raleigh Sr. and Katherine Champernowne. They had three children: a son named Carew; a daughter named Margaret; and the youngest of all the children, Walter. Walter Raleigh Sr. also had several children from his two previous marriages. Little is known about Raleigh’s early years. His elementary education may have included being tutored by a local vicar and perhaps a brief attendance at the school of Ottery Saint Mary. Young Walter grew up during a time when England was divided between two religions: Protestant and Catholic. Raleigh’s family was highly Protestant in their religious beliefs; they had a number of near escapes during the reign of Queen Mary I of England, a Roman Catholic. In the most notable of these, his father had to hide in a tower to avoid execution. As a result, Raleigh developed a hatred of Roman Catholicism during his childhood, and proved himself quick to express it after Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant, came to the throne in 1558.1

In 1569, Raleigh, as an English volunteer, served in the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) on the side of the Protestant French Huguenots.2 In 1572, Raleigh’s name appeared in the register of Oriel College, University of Oxford, but he never earned a degree. In 1575, he was studying law at the Middle Temple, one of London’s Inns of Court.3 In June 1578, Queen Elizabeth granted Raleigh’s half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a six-year patent to explore North America and to plant colonies in areas not claimed by other European powers. Raleigh was a member of the expedition which never made it past the African coast.4 In late 1580, Raleigh went to Ireland to help suppress a Catholic uprising in Munster, where he remained until December 1581. His actions were brought to the attention of Queen Elizabeth. He received many honors over the years, including estates in Ireland; he was appointed captain of the Queen’s Guard, and became a member of Parliament. He was knighted in 1585, when he officially earned the title of Sir Walter Raleigh.

Voyages

Principal Voyage

In April 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh, under patent, sent Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlow to establish the first British colony in North America. They landed on Roanoke Island (present-day North Carolina), and named the land “Virginia” in honor of the virgin Queen Elizabeth.5 In April 1585, Raleigh dispatched 108 men to establish a colony on Roanoke Island. However, quarrels, disorganization, and hostile natives resulted in the colonists returning to England by June 1586. They brought with them tobacco, and presented it to the queen’s court, calling it “brown gold.” Two weeks later, Sir Richard Grenville arrived at Roanoke Island with supplies and more colonists. He left 15 men to maintain England’s claim to the land, returning to England with the rest.6

In 1587 Raleigh sent more than one hundred colonists, under the leadership of artist John White, to the New World. The new colonists arrived at Roanoke Island on July 22, 1587. However, none of the men Grenville had left there were found alive. In August 1587, White’s granddaughter, Virginia Dare, was born. She became the first English child born in America. White soon returned to England for supplies. His return to the colony was delayed until August 1590.7 When he finally returned, he found no trace of the colony with the exception of the word “Croatoan” carved on one tree and the word “Cro” carved on another. The fate of the “Lost Colony,” as it has been called, has remained a mystery to this day. He returned to England where, in 1592, he secretly married Elizabeth “Bess” Throckmorton, one of the queen’s maidservants. The discovery threw the queen into a jealous rage. The couple was briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London.8 Upon release, Raleigh hoped to recover his position with the queen. Legend told of a lost city of gold called El Dorado. Raleigh intended to find and capture this city before the Spanish did.

Subsequent Voyages

On February 6,1595, Raleigh’s fleet began their journey in search of El Dorado. It was rumored to be located somewhere in South America, beyond the mouth of the Orinoco River, in the mountains of present-day Guyana. This area was within the heart of Spain’s colonial empire. The English expedition landed in Trinidad and captured the Spanish leader, Don Antonio de Berrior. Berrior had also spent time looking for El Dorado, and Raleigh convinced him to tell the Englishmen what he knew about the fabled city. Raleigh and his men headed up the Orinoco on rafts and small boats. Relying on native guides, Raleigh’s expedition made their way into the hot, humid jungles of South America. The thick jungle flora and fauna made parts of the journey difficult to travel through. Raleigh documented many of the plants and animals he saw. He described the birds, “of all colors, some carnation, some crimson….”9

They traveled up the Orinoco River which then turned into the Caroní River. Here, at a native settlement, Morequito, they encountered a village ruled by a chieftain named Topiawari. He told Raleigh of a rich culture living in the mountains. Raleigh believed that the culture was once a part of the rich Inca culture of Peru and that it must be the fabled city they were seeking. Raleigh and his men continued on their way for several days. Yet heavy rains soon caused the rivers to become too rough to travel. With supplies running low and little evidence of El Dorado to be found, Raleigh and his men soon returned to England in August 1595. Raleigh’s expedition was viewed as a failure. Yet, he did not give up his belief that the city of gold existed. In 1596, Raleigh published The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana: With a Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa… Etc. In it, he describes much of the regions he explored in South America, including rivers, plants, and animals.10 The book was very successful; yet, Raleigh was still unable to find the support he needed to continue his search for El Dorado. It would be more than 20 years before Raleigh would once more go in search for the city of gold.

Later Years and Death

In 1603 Raleigh was accused and convicted of plotting to overthrow Queen Elizabeth’s successor, King James I of England. The king sentenced Raleigh to death. This was soon reduced to life in prison, and Raleigh spent the next 12 years locked up in the Tower of London. There he wrote the first volume of his History of the World in 1614.11 Raleigh was released from the Tower of London in 1616, and was allowed by the king to search for gold in South America. On June 12, 1617, Raleigh began his second attempt to find El Dorado. After arriving in South America, illness prevented Raleigh from leading his men up river. Before leaving, James I told Raleigh not to attack any Spanish settlements, in order to make relations between the two nations better. However, his men attacked one of the Spanish settlements. Although Raleigh was not directly involved, the Spanish demanded Raleigh’s death upon his return to England. After several months of searching, Raleigh once again had failed to find El Dorado. After his return to England, Raleigh was arrested, and then executed at Westminster on October 29, 1618.

Legacy

Sir Walter Raleigh is among those legendary maritime adventurers of the Elizabethan Age known as ‘Sea Dogs,’ privateers and explorers that also included Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins. Raleigh may not have successfully colonized the New World for England as he hoped and the Roanoke colony’s disappearance is still one of history’s greatest mysteries. But his expeditions provided a wealth of information for future successful English colonization efforts. His efforts gave these failed colonies the name “Virginia.” He is credited with popularizing tobacco in England. His attempts to discover the legendary city of gold, El Dorado, allowed him to explore and recount many aspects of the South American landscape. The capital city of Raleigh, North Carolina, bears his name and honors his legacy.

Images

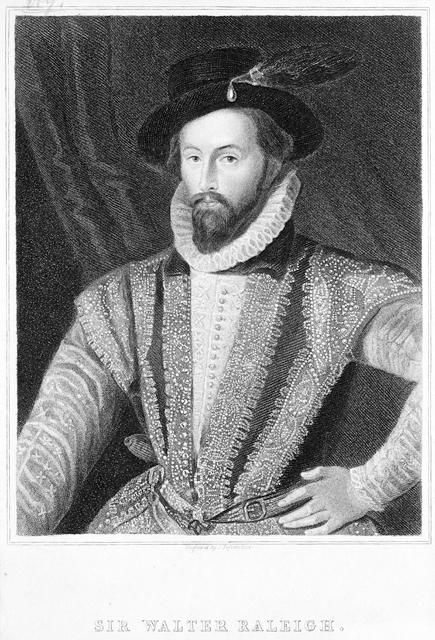

- INSCRIPTION: SIR WALTER RALEIGH, OB. 1618, from the Original of Zucchero, in the Collection of the Most Noble the Marquis of Bath., Engraved by H. Robinson, London, Published Jany 1, 1829, by Harding & Lepard, Pall Mall East (credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park catalog#-1940.0230.000001)

- Page from Newe Welt Und Americanische Historien published by Johann Ludwig Gottfriedt in 1655 showing Sir Walter Raleigh attacking and burning St. Joseph on Trinidad in 1595. The image shows the town burning in the background and a Governor Antonio de Berrio being escorted to a small boat that will carry him to Raleigh’s flagship. (credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park catalog#-1945.0208.000001)

- INSCRIPTION: Sir Walter Ralegh Knt., Captain of the Queens Guard, Land Warden of the Stanneries, Lieutenant General of the County of Cornal, Govenor of the Isle of Jersey &c obt. 1618, G. Vertue del. et Sculpt credit: The Mariners’ Museum and Park catalog#-1951.0488.000001)

Endnotes

- Biography.com, Eds., Biography.com, “Walter Raleigh Biography,” accessed July 12, 2017, https://www.biography.com/people.

- Kristin Petrie, Sir Walter Raleigh (Edina: ABDO Publishing Company, 2007), 8.

- Ibid, 9.

- Brendan Wolfe, Encyclopedia Virginia, “Sir Walter Raleigh (ca. 1552-1618),” Accessed July 13, 2017, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Raleigh_Sir_Walter_ca_1552-1618#start_entry.

- Susan Osborn, What’s in a Name? (New York: The Philip Lief Group, Inc., 1999), 675.

- Brian Belval, A Primary Source History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2006), 35.

- Ibid, 53.

- Steven P. Olson, Sir Walter Raleigh: Explorer for the Court of Queen Elizabeth (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2003), 72.

- Ibid, 84.

- Mark Nicholls and Penry Williams, Sir Walter Raleigh: In Life and Legend (London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011), 111.

- Nicholas Popper, Walter Ralegh’s “History of the World” and the Historical Culture of the Late Renaissance (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 1-2.