Tektite

Ship

Modern

Quick Facts:

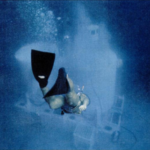

Submerged underwater, the Tektite laboratory allowed scientist to explore the ocean floor longer and more up close.

Introduction

Tektite [tek – tīt] was an underwater laboratory. Though not a traditional vessel, this unique habitat allowed small crews of scientists to stay submerged in the ocean for extended periods. Much like astronauts work in outer space, these underwater scientists could spend hours on the ocean floor exploring and conducting research like never before.

History and Development

Early maritime exploration was often done on and by ships sailing on the water. Sailors would spend months traveling and living on these vessels recording their work. Modern maritime explorers today can now actually live in underwater vessels to study life in the oceans. The Tektite project was a group effort between the United States Navy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), General Electric, and the Department of the Interior. The laboratory was built in 1969 and submerged 50 feet in the waters of off the Virgin Islands in the Great Lameshur Bay. “Tektites” are green, glassy balls found on the ocean floor which scientists believe fell from space – this is how it got its name.

The Tektite I housed a group of four scientists called aquanauts.They would swim out and study a variety of sea life, but especially focused on the spiny lobster – how it moves, eats, and survives.1 The four men were underwater for sixty days. This beat the previous 30 day world record for time spent underwater. In 1970 Tektite II was launched with an all-female crew, lead by Sylvia Earle, known as “Mission 6.” They documented 154 species of marine plants, including 26 species not yet discovered in the Virgin Islands.2 Despite the successes of both Tektite I and II, NASA and its collaborators ended the program in 1970, mostly due to costs.3 Tektite set many records including: the first long-term scientific mission in the sea, longest saturation dive, first NASA mission to include women, and only mission with an all-female crew.4 Tektite and other underwater laboratories are not your regular maritime vessel, but they are still important to maritime exploration.

Design

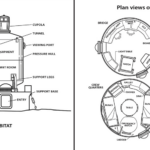

Tektite was made to be a home and research vessel to divers during their time under the sea. The Tektite I habitat was designed and built by General Electric Company. It had cables attached to a shore-based system which provided air, water, and power.5 It had to be strong enough to withstand the pressure of the ocean. The farther down you go, the heavier the pressure will be. It was a pair of two 18 foot steel tanks connected by a tube that the aquanauts could move through from tank to tank.The crew’s quarters were four cramped sleeping spaces, that had plexiglass ports to look out.6 The left tank contained the crew’s quarters and the bridge or command center. The right tank was the machine room and the wet room where the crew would put on and take off their gear. The right tank also had a cupola at the top where the aquanauts could look out. A cupola is like a small dome usually on the top of a larger roof or ceiling. A base camp was located on the surface as well. Here, all other crew, except the four aquanauts, would live and work here to monitor the Tektite habitat and crew below.7

Endnotes

- Stan Wayman and Reg Bragonier, “The Longest Dive,” Life Magazine, March 7, 1969, 33.

- Beth Baker, Sylvia Earle: Guardian of the Sea, (Minneapolis: Lerner Publication, 2001), 52.

- James Merle Thomas and Meghan O’Hara, “Tektite Revisited, Bringing the Final Frontier Back Home: NASA, Aquanauts, Anechoic Chambers, and the Problems of Modern Living,” Triple Canopy Magazine, accessed July 28, 2017, https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/issues/13/contents/tektite_revisited.

- “NASA’s Tektite II Undersea Habitat: An Interview with Aquanaut & Engineer Peggy Lucas Bond,” Spaceflight Insider, December 13, 2013, http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/space-flight-news/nasas-tektite-ii-undersea-habitat-an-interview-with-aquanaut-engineer-peggy-lucas-bond/.

- Susan E. Reichard, Who on Earth is Sylvia Earle?: Undersea Explorer of the Ocean, (New York: Enslow Publishers, 2010), 35

- Wayman and Bragonier, “The Longest Dive,” 34

- D.C. Pauli, et al., “Project Tektite I: A Multiagency 60-Day Saturated Dive Conducted by the United States Navy, The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of the Interior, and the General Electric Company,” (PDF), Office of Naval Research, accessed August 9, 2017, 10-11 http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/773351.pdf

Bibliography

Baker, Beth. Sylvia Earle: Guardian of the Sea. Minneapolis: Lerner Publication, 2001.

“NASA’s Tektite II Undersea Habitat: An Interview with Aquanaut & Engineer Peggy Lucas Bond.” Spaceflight Insider. December 13, 2013. http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/space-flight-news/nasas-tektite-ii-undersea-habitat-an-interview-with-aquanaut-engineer-peggy-lucas-bond/.

Pauli, D.C. et al. “Project Tektite I: A Multiagency 60-Day Saturated Dive Conducted by the United States Navy, The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of the Interior, and the General Electric Company” (PDF). Office of Naval Research. Accessed August 9, 2017. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/773351.pdf.

Reichard, Susan E. Who on Earth is Sylvia Earle?: Undersea Explorer of the Ocean. New York: Enslow Publishers, 2010.

Thomas, James Merle and Meghan O’Hara. “Tektite Revisited, Bringing the Final Frontier Back Home: NASA, Aquanauts, Anechoic Chambers, and the Problems of Modern Living.” Triple Canopy Magazine. accessed July 28, 2017. https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/issues/13/contents/tektite_revisited

Wayman, Stan and Reg Bragonier. “The Longest Dive.” Life Magazine, March 7, 1969

Gallery